After his older brother was baptized in church, little Tommy sobbed all the way home. Three times his father asked what was wrong.

Finally, Tommy replied, “The pastor prayed that Billy would be brought up in a Christian home. I want him to stay with us!”

Every parent enjoys a moment of delight, often brought on by something a child says. It’s true, kids do say the darndest things! But raising godly children is serious business. So serious, in fact, that it is a pre-eminent qualification for spiritual leadership in the church.

The apostle Paul addresses the issue twice.

He must manage his own household well,

with all dignity keeping his children submissive,

for if someone does not know how to manage his own household,

how will he care for God’s church?

—1 Timothy 3:4-5

. . . appoint elders in every town as I directed you—

. . . above reproach,

the husband of one wife,

and his children are believers

and not open to the charge of debauchery or insubordination.

—Titus 1:6

Why is this so important?

1 Timothy 3 explains why the condition of a person’s home is an important qualification for spiritual leadership. The question in verse 5, “how will he care for God’s church?” links a well ordered home – “manage his own household well” and “keeping his children submissive.”

How a spiritual leader in the church leads his own home is a preview of how he will lead “the household of faith.” John Stott observed this foreshadowing: “The married pastor is called to leadership in two families, his and God’s, and the former is to be the training ground of the latter.”

Interlocking Families

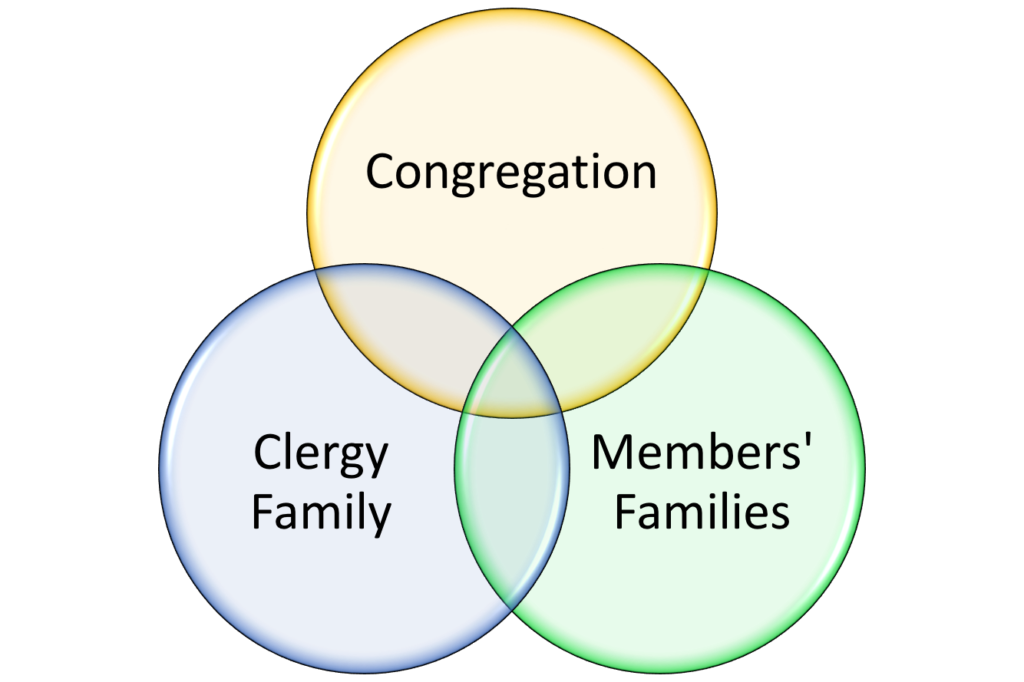

Pastors and other church leaders participate in three interlocking subsystems: their own family, the families of church members, and the church itself (which behaves like a family). When we experience a disturbance in any of these subsystems, we may feel anxiety that we carry into the other systems.

A pastor will feel anxiety and stress when his teenaged son is arrested for DUI. Unless he is especially mindful (and exceptionally disciplined) he will carry those emotions into the congregational subsystem. If so, church members may experience the pastor as being suddenly less attentive to their needs, as having less energy to carry the workload, or as irritable and short-tempered.

His ability to lead in one sphere (the church) has been diminished because of trouble in another sphere (his nuclear family).

We can’t plan for painful or catastrophic events – not in our own lives and certainly not in anyone else’s life. We deal with those issues as they occur.

But our focus here isn’t on how a pastor or other spiritual leader deals with crisis. Rather, we’re considering how they conduct life in their own families because they will function similarly in the “church family.” The one who provides leadership, guidance, and discipline at home (which is evident in a successful family that achieves its goals with minimal dysfunction) will employ those same behaviors when leading in church.

When a spiritual leader goes off the rails

Sooner or later every pastor will have to deal with a spiritual leader who’s suddenly derailed. When that happens, your challenge will be to formulate a “redemptive response” to this new and dysfunctional behavior. As you think this through, take some time to “zoom out” to look at all three of his subsystems.

Consider the possibility that the complain (or misbehavior) are symptoms. Dig a little deeper and see if you can’t get at the underlying cause of this new and unwelcome behavior.

One way to do that is to answer a series of questions:

1. What is the issue that needs resolution?

Describe the complaint that has been raised or the problem behavior that has appeared.

In one church I served the Finance Secretary began expressing dissatisfaction that the new people and the new initiatives were changing the church. “It’s not the same place!”

2. Who are the people and relationships involved?

Once you’ve identified the presenting problem, try to sketch out that how the parts of that person’s various subsystems interact.

One protege whom I mentored experienced trouble when his church entered a period of rapid growth. Parents began complaining that the quality of the Youth program was deteriorating. He investigated the issue and discovered the following subsystems:

- Complainants who had been in the church before the pastor was called.

- Previous pastors who engaged in maintenance rather than missional ministry.

- Congregational attitude that unbelievers are God’s enemies rather than objects of his love.

- Many new families were “unchurched” who didn’t “get” the church’s culture.

- Loudest complainants were homeschoolers who wanted to cocoon their children.

Bear in mind that churches are made of people who relate to one another emotionally and functionally. On top of that, relationships between people in church are colored and shaped by other relational systems (nuclear families, extended families, work, etc.)

3. Why has this become a problem at this time?

If you want to pinpoint the underlying cause (rather than continually respond to symptoms) you have to figure out “what’s changed?” in these interlocking systems.

Once you’ve identified that, you’re getting closer to the appropriate response.

In the case of the Financial Secretary, my investigation revealed that his wife was dealing with escalating fears that he would die suddenly (he had a history of heart problems) and leave her a widow. Her anxiety – a feeling that life was spinning out of control – began to weigh on him. This, combined with his own growing realization that he had no control over the time of his own death, created anxiety.

The appropriate response was to help husband and wife change their family system. They needed to learn to walk more closely with God and embrace his good and gracious control over their lives. (This was an interim assignment; I left shortly after this issue emerged so I wasn’t there to see how it finally resolved. But I’m confident it was the right approach).

In the case of the complaining parents, the problem emerged when the “before the pastor was called” group of parents sensed control of the Youth ministry slipping from their grip. (In that pastor’s first two years the church had grown from an average attendance of 35 to more than 200).

Rather than respond to their anxious calls that the pastor “do something” he patiently worked with them to change the church system and their family systems. He taught and counseled the church about their missional responsibility to the Lord. Rather than being a “safe place” that protects us from “those people”, he taught them that the church is a mission station in a hostile culture.

He leveraged the church system’s anxiety to introduce meaningful change. He addressed the underlying problem (inward focus) rather than the symptom (quality of the Youth ministry).

As it turned out (I’m sure you can guess what happened), the complaining families left the church. But the pastor had worked deftly to introduce significant change in the system. The church recovered the loss fairly quickly and continued to grow.

Don’t deal with “difficult” people, change the system

Pastors and spiritual leaders should avoid stewing about and trying to fix “difficult” people. When we focus on their complaints or behaviors we’re actually affirming their dysfunction.

Bottom line

Good spiritual leadership doesn’t negotiate with bad behavior. It doesn’t try to manage carping and complaining. It doesn’t tolerate gossip. It does not overlook building alliances and coalitions.

Good spiritual leadership exercises guidance, love, and discipline – all grounded on firm, biblical principles.

We learn these leadership behaviors in our family of origin. We exercise them until we become skilled in our own nuclear families.

And this is why a well managed home with well-behaved children is a primary qualification for spiritual leadership in the church.